After a rather bleak time psychologically in Bogota and the the high intensity and wonderful month of backpacking with Selina, I was feeling worn out, to say the least. I wanted to rest, and I needed to plant some roots somewhere I felt happy and was diverse enough from my regular habits that I felt fulfilled. As always, my life provides, and I found myself in Taganga, a place I will return to and would have spent the rest of my days if I wasn’t such a rootless fool.

The Power of Suggestion

I finished my journey with Selina in a Selina Hostel in Cartagena, a city of filthy debauchery. With a history of piracy that still hangs glaring and ominous over the port like an ever-present architecture. As my time came to a close there, I needed my next place to live, and I also needed to renew my visa. However, there was no way I would be staying in Cartagena, and I couldn’t face the mundanity and concrete of a city like Bogota.

I needed to be by a city with an immigration office so I could extend my visa, but Santa Marta was out of the question. It is yet another washed-up port town. However, looking at google maps, someone had marked a little spot just south of Santa Marta, tucked away in a cove, accessible by a small winding mountain road. I felt like I remembered who gave me the suggestion, and I am not in the habit of marking down pointers from dullards. Pictures looked beautiful, and there was little to no information about it, bar it being a small fishing village, so my mind was made up.

Airbnb turned up a few spots around the place, but honestly, it was hard to gauge the size of the area, let alone what beachside meant. I found a spot ‘Up the Hill’, shared with a woman and a few others, and booked in for a few weeks. It seemed ideal; it was close enough to Santa Marta to sort a visa, and it had a pretty untouched beach to play with. I packed up, hopped on a coach, and made my way along the Carribean coast to the unknown.

Not your typical beach town

Rocking into Santa Marta bus station, again, was just confirmation of why I wasn’t staying there. It fucking sucks. But a taxi from there to Taganaga only set me back a fiver, so I jumped in the back, and we left as quickly as we could.

An aside on the Taxis of Colombia

Uber is illegal, as is Didi, but there is an alternative if you don’t want to break the incredibly flaunted law. You can use LibreTaxi or hail one of the yellow cabs that rattle around everywhere, and I use rattle correctly. These cabs they use are all made by the same manufacturer, I presume, and must be part of the reason Uber, etc, is illegal. There has to be some government agreement keeping the cab company in business because I have never been in such decrepit cars.

They come in many shapes and sizes, but they all have one thing in common. They sound like they have been made of aluminium and have been glued rather than bolted together. Being inside one is both hilarious and terrifying as you struggle to hear the driver scream over the sound of rending metal and disk brakes that sound like they’re made of rock and gunpowder. The various rides I have taken in these have shortened my spine by a solid few inches.

Yellow Taxis of Colombia are an experience, expensive, and a huge contributor to waste and CO2 levels. But I digress.

Cont…

We left Santa Marta and made our way out, around a winding road that took us ever further away from the city. One side was the sheer side of a mountain, and on the other, a drop-down into Favellas and rocks. I had read that the walk, although possible, was highly inadvisable due to the bandits that live in the mountains, a threat I found out to be all too real.

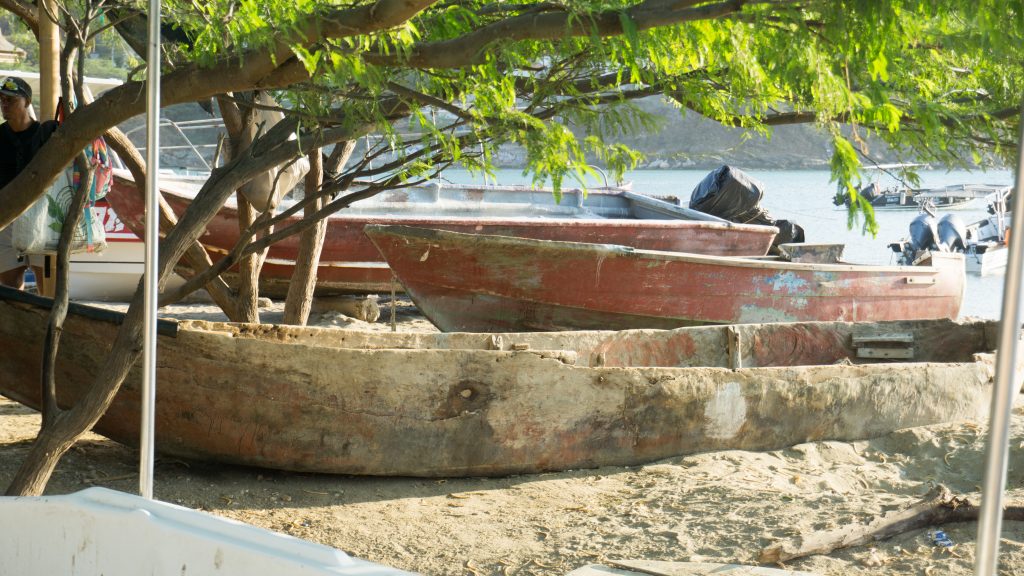

As the car rattled and clanked its way along the winding road, we finally came around one of the final corners, revealing the view that would be my own for over two months. Taganga and its stunning, rocky, secluded cove opened up beneath us. The beach was lined with fishing boats, and backing up from the wide, curved beach, was maybe only a mile or two of small, clustered homes. I saw bamboo rooves, small winding streets, and not a single high-rise tourist resort anywhere. Taganga was tiny, and from where I was, rolling my way towards it, it looked remote enough to be perfect.

Nervous Locals

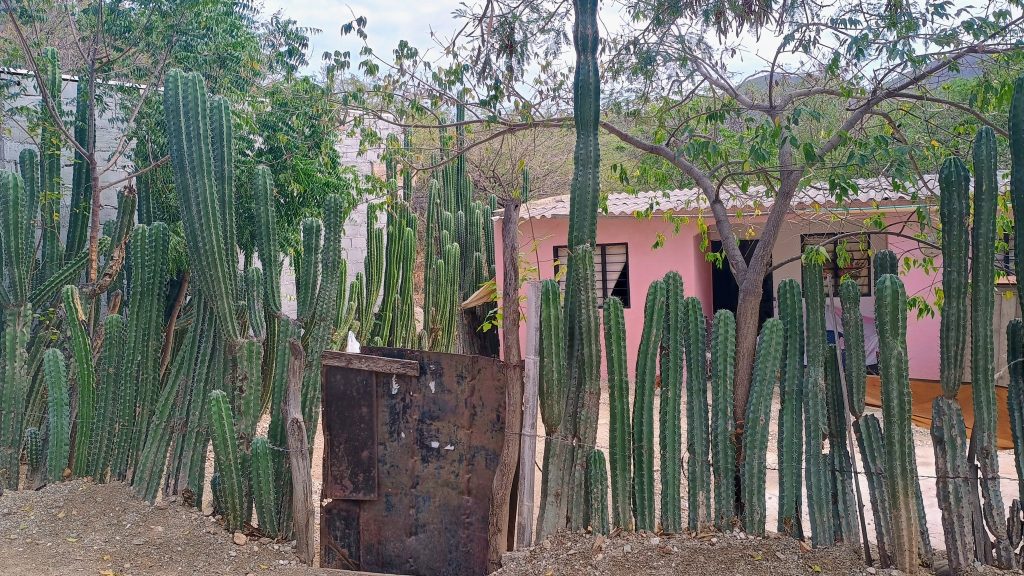

The old boy who drove me from Santa Marta to Taganga was about 90 years old, but it didn’t stop him making sure he did his job to the best of his ability. As mentioned before, the car he was driving was being held together by the Immaculate Heart of Mary swinging in his rearview mirror. But, once we got into Taganga, it was apparent that the idea of tarmac and concrete was one the locals had given a go but decided against for the most part. There was a single track of paved road running in a cross shape through the whole town, but anything else coming off this was rutted dirt track.

This puts most taxis off coming too far into the town and keeps it the way it should be. Most of the locals ride motos or drive Land Rover produced before the dissolution of Gran Colombia. However, ever the good driver, my pilot insisted he would make sure I got to my door. He was insisting that I was not safe to be walking the streets alone, determined that I would be mugged and shot the minute I stepped foot into the street at 5 PM.

I hopped out of the car where the Airbnb said it was and obviously wasn’t. After contacting my host, she gave me walking instructions to get to the house. My cab driver crawled his car over the foot-deep potholes and rocks, mere inches behind my feet, as I walked through the blistering heat. I had already paid the man; he was just obsessed with the idea that I was facing certain doom.

Nevertheless, my host popped out from a side alley, and he was able to breathe a dusty, fume-filled sigh of relief, knowing another Gringo had avoided death under his watchful and diligent eye.

Blowy as Fuck

Taganga is built into a valley that funnels down into the sea, creating a natural cove with calm waters and a beautiful central sunset. However, the wind that comes screaming down the mountain that backs the town is a force to be reckoned with. I was living up the far side of that hill, and boy, was it an experience.

I chose the Airbnb I was staying in for its floor-to-ceiling windows on half of the walls. The view was spectacular, looking over the whole of the town from up on the hill, and I could sit out on my balcony, working with the view out in front of me. In the day, the wind was minimal, with a few gusts here and there to dispel the phenomenal heat that would often reach an air temp of close to 40 Celsius.

However, as I lay down to sleep and the pressures of the valley changed, the monsters that lived in the jungles over the crest of the mountain rose and started their mischief. The gale that would blow around the loose, single-glazed windows surrounding my head was cacophonous. It shook the whole building and had me submitting to the idea of being showered with glass, rubble, and the remains of whatever roof was left. It would scream through the house, lifting anything not weighed down. In time, it became a comfort, and I was able to fall asleep to the sensory-deprivating sounds of wind and storm.

The wind was often a welcome break in the day from the heat. This was a town that knew its limits, and they came between about midday and 3.30. If you’re out then you don’t live in Taganga, and you deserve the dehydration and mind-bending heatstroke. The sun comes down so hard that you can even feel it feet under the water. This made working easier because usually, the sight of an ocean from my workplace is enough to drive my mind mental, but knowing I could only dip in the morning or at about 2 pm onwards meant my restlessness was briefly subdued.

Tranquility Sets In

After a relatively high octaine month with Selina and my own time in Medellin beforehand, I had become somewhat accustomed to the high-speed lifestyle. Moving day by day, filling time with new adventures and excitement, had become the norm, and it had been great. But, as with any time of speed and stimulation, it takes a while to slow back down again and learn to live in the moment. But with Taganga, it didn’t take all that long.

I slowed down so hard in the small cove of Taganga that it took me almost six weeks to leave, even to the next town. I didn’t just become settled; I became embedded like a stubborn splinter. I had everything I needed, was needed by nothing, and felt no need for nada. Taganga provided what I wanted, and because of this, my life became small, and my mind started closing the auxiliaries and extras required for a place with high demand.

Days became somewhat routine in the most perfect possible way. An early 6 am wake-up was usually brought on naturally by the sun breaking over the mountain and heating my room to a slightly more than pleasant temperature. Just enough for me to roll over, crack the huge windows, show the populace of the sea and the town my balls, and climb into a shower that was still coming from a cold rooftop water tank.

My next decision was whether to make myself a bowl of local fruit and yoghurt accompanied by the endless Tinto made by the host or make the slow walk down the dirt roads to a local spot tucked into someone’s home for a big Colombian breakfast costing no more than a smile.

Depending on my work that day determined just how long I would laze before starting work. Either way, by about 8/9, I would be ready to start and then spend the rest of my morning typing away. By midday, the sun would be up, and I would be ready for lunch, which, more often than not, I would head back into town for.

Menu Del Dia in Colombia costs about £2 to £2.50 and consists of rice, beans to the house specifications, a protein, a small salad, and a little extra like plantain or some kind of meat sauce. This is all washed down with the drink of the day, usually Aguapanela, which consists of unrefined sugar cane, lime, and water. It’s cheap and delicious, especially in the heat. The day would pass me by, sitting in the shade of a small, family-run restaurant.

Sometimes I would meet someone in these lunch moments, and sometimes I would just sit by myself, and let my mind wander with the dust clouds and unschooled children. Once my food had settled and I had paid my bill I had one of the biggest decisions of the day to make. Do I walk the 5 minutes to the beach to sunbathe and swim, or do I head back and do more work? The problem is that going to the beach might mean I don’t leave the beach. There are cold drinks and good people there, and life often gets in the way of work.

Either I went to the beach, swam in the heat of the day, fried my long-suffering, still suncream-free skin, and went home for an hour or two more writing, or I got distracted. Either way, I was going to end up on the beach by sunset, watching the phenomenal views that most people visit Taganaga for before heading home. The majority of tourists there come for that alone and head home after a few hours. More fool them, I guess.

The evening would consist of a meal and beer at one of the restaurants around the place. Admittedly, the variety was pretty limited, and my body was screaming for fibre after the two months, but it wasn’t bad, and the fish was exquisite.

Finally, onto a Bodega for cheap liquor and beers until bed. I was gifted with wonderful company for my entire time due to the locals and that of a pal. It didn’t take much to convince them to join me in my little slice of life.

Landon

I know I wax lyrical about a lot of people, but that’s because I like them, and I like waxing lyrical, so fuck off. Besides, Landon was an exceptional person, and a dear friend I hope to never lose, although I doubt very much I will.

We met in Medellin when he stayed with me in a house with a Norwegian Bulldozer and a Colombian oddity. The latter was too much for Landon, so he left, but the friendship had already been solidified over a joint love for drinking rum out of a carton in plastic chairs outside late-night bodegas and putting the world to rights. Well, I know he loves two of those, but the plastic chairs and cheap bodegas were my usual stipulation.

Throughout our time in Medellin, we spent days and many nights together, meeting folk, visiting spots, and nattering the whole time. He is an interesting man with a patchwork of experience and vast, off-kilter intellect that kept me on my toes. He is filled with ideas, opinions, and intelligence, but he never loses his temper when challenged and will always dig into a topic. This, for me, was incredibly refreshing. I feel like I had been in a bit of an intellectual dry spot when it came to company, mostly due to the language barrier.

We parted ways, as is always the case, and I went travelling with Selina, and he, too, made his trips. So, it was to my absolute delight when he called me from no other than Santa Marta, telling me how fucking foul it was and that even going out to buy water after 6 PM had him boxing his way home. Come on over, bud; the waters are cold, the air is hot, and the beers cost pennies; you’ll love it.

He was there by the evening. He had packed up his Airbnb and moved to Taganaga within a day or so. This was typical of Landon, who lived by the minute and politely never took no for an answer. I have never seen anyone with so little Spanish change so many set menus to their liking.

He embedded himself in Taganga, and eventually, I ended up moving next door to him in a much nicer apartment than my last, with A/C and my own space. He was, in no small part, why Taganga will forever be one of the best places I have lived the last few years, even if he did nearly get shot to death in the process.

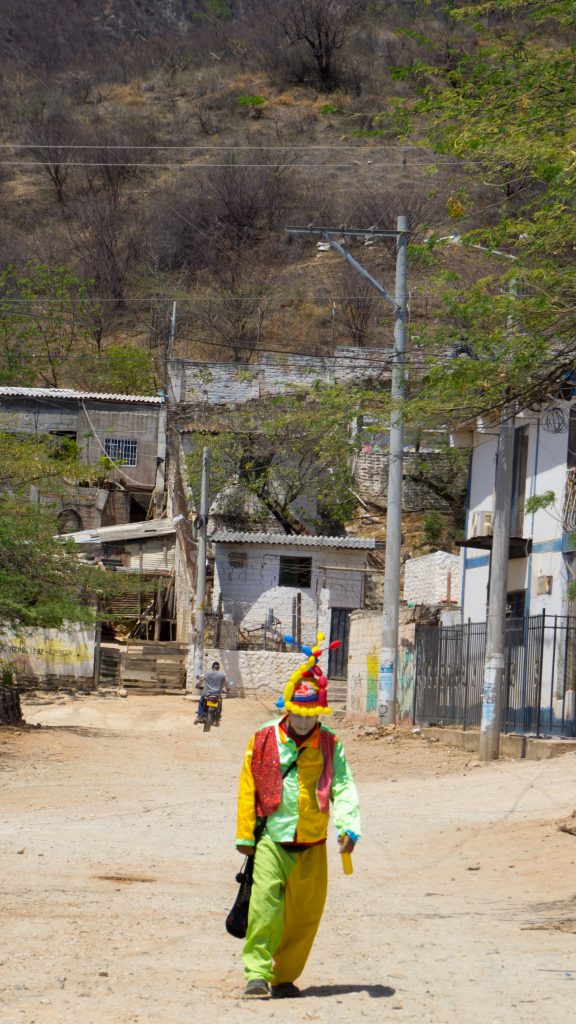

Taganga Cultura

I had been warned about the Colombian Caribbean folk, and when other Latinos tell you someone is loud, it really means something.

Pico Sound Systems

When I first arrived and lived up the hill away from the centre, I was kept awake and disturbed for about 4 days by a blaring sound system. I mean, this thing was phenomenally loud, and it wasn’t even that close. It sat a street or two away, down the hill, and yet it rattled my windows from about 9 am to probably around 11 pm, depending on how pissed the players were.

This Soundsystem, called a Pico, is native to the land of Colombian Caribe folks and is worshipped in force in Taganga, where there is almost one per household. They sit about 6 feet tall and maybe 4 and a half feet wide and can play music at a level that would put a lot of stadiums to shame. They are designed to play Colombian Caribbean music specifically, which is a mix between Mariachi and god knows what. You can get an earful of it here.

These sound systems are used for celebrations of any kind during which the locals will place them on the street and, at full volume, play music into the air. Together, the family will sit inches from it in their plastic chairs, blasting inhuman quantities of drink and, I expect, Colombian nose fuel. For days they will sit, unable to speak, only able to drink, in front of these Pico sound systems, often passing out with them still blaring until someone falls off a chair and remembers to switch it off.

I often walked past them in the morning, on my way to breakfast, with 4 or 5 semi-dressed folks still in their chairs, perched around the monoliths, surrounded by hundreds of beers. As soon as they awoke, the tunes would be back, and the empties would be traded in for cold boys.

One of my favourite things about it was how many people, connected to the speaker by phone, wouldn’t have their notifications turned off. So, every so often, sometimes very often, a notification DU DU DU DU DUUUU would blare across the streets, knocking birds out of trees, and turning the encroaching monsters back from the cusp of the mountain. However, they wouldn’t disable notifications after this, it would just continue.

As annoying as this sounds, after the first week I was so used to it. After a few weeks, I stopped hearing it. After a month, I kind of loved it, and if I don’t have one at my next week-long party, it’s just not going to feel all that special.

Fish stock

Taganga is a fishing village, and it will remain that way as long as the locals have anything to say about it. From what I understand, a few families own quite a bit of land, and they have their rivalries. The rest of them live in their small but idyllic world, fishing, farming, and raking in money from the tourists.

I don’t want to sound condescending, and I am far from someone who has their life in any kind of admirable order. Nor would I ever commend the shambles of a country I come from or wave its flag as somewhere people should aspire to emulate. So, the observations I make of the people of Taganga are made impartially and without disdain. I know no better and would never profess to.

The locals who have lived off the sea and the land of Taganga have no interest in changing this lifestyle. It provides all they need, and the trickle of tourists who come for a few days, but usually just one, bring in a little extra income, and that is quite alright by them. Very little has been done to accommodate tourism, and from what I understand, little is done to change the professions of the younger kids of the fishing folk. They’re happy with the ways things are and see no need to change it.

I see completely where they come from. I lived there for the short time I did, without family, with a great but small friend group, and really only on the surface. For me, it was paradise, which would only be more pure if I was also surrounded by my loved ones, a deep history, and a land that fed and clothed me.

To some, the lack of desire for ‘progression’ and ‘intellectual development’ may seem backward and stubborn, but having been around it and tasted just a morsel of what it could offer, I say if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it. The scum and filth of tourists in Santa Marta and Cartagena would put me off ever welcoming that kind of ‘Progression’ too.

Speaking to a wonderful Argentinian couple who washed up in Taganga a few years ago and now run the bombest pizza restaurant and Hostel, maybe in Colombia, it was interesting to find out their role with the local children. They had taken a number under their wing, often entertaining them and giving them odd jobs throughout the day. The kids didn’t go to school, and while their parents did what they did in the days and evenings, they would come to the hostel for tasks and entertainment. Now, again, it’s only my place to observe, but the amount of free roam kids at all times of the day and night was always interesting. They were only outnumbered sometimes by the stray dogs.

Might go get stabbed, dunno

So Taganga had a reputation I heard of before I got there, which was only reinforced while I stayed there. However, I live outside the universe somehow and have now, currently, lived in a number of the most dangerous cities in the world and come out unscathed. I’m not jinxing it because it has nothing to do with luck. I am fucking enormous, incredibly physically intimidating, and look so poor most pickpockets actually leave things IN my pockets. Honestly, it’s mostly the latter.

Either way, Taganga has a reputation for a few things: street crime and mountain bandits. Both of these are absolutely real, and I have heard about them both firsthand.

Steel Magnolia

The first instance was from Landon himself as he went out for his lunchtime fresh fried fish at one of the beachside huts. He was tucking into the delicious meal when he noticed a slight commotion going on. Now, being a man of the United States of America, he has been trained to deal with live shooter situations since before he was able to mindlessly recite the pledge of allegiance, so luckily, his USA sense started tingling.

From the corner of his trained eye, he spotted cold steel as one of the chancla-wearing, board-short sporting locals whipped a pistol from his waistline. In seconds, Landon had hit the ground as the commotion reached a fever pitch and people started pushing back from this clearly enraged man. From the footage I later saw, the folks working in the hut and on the street were initially just perturbed in a ‘Not this shit again’ way and then started running when he licked off some hot lead.

By this point, Landon had pitched himself over a small wall that runs just beside the beach, putting something in between himself and the shooter. Even after the gun had been fired, the locals still seemed much less fussed than I certainly would have been. I have heard plenty of gunshots in my time, but being beside one is something I am blessed to never have been.

The man cleared off, and service quickly resumed. Landon picked himself up, checked his grazes, and continued with his meal, a little shook up but somewhat reassured by the lack of stress from the staff and locals. Typically, there were no police; they typically do nothing but clear the beach for half an hour at night.

According to the people in the town, the two warring families like to pop shots at each other every so often. It keeps tourism down, keeps the rivalries up, and ensures house prices stay at an all-time low.

Bandido de Montaña

A short walk from Taganaga is a whole collection of beautiful coves. They have no electricity but are stunning. On the weekends they are teaming with families and people looking to get away from Taganga. It is possible to walk for a few hours across the dusty mountainside path, clambering over rocks and cacti, past ruined developments destroyed by earthquakes and landslides.

The reward is crystal clear waters and often a private beach. These little coves are ancient fishing spots still used by the indigenous folk, and it’s a marvel to watch them still pull in their huge coastal nets in the blazing heat of the day. However, you have to make sure you don’t get caught after dark because that’s when the banditos descend from the mountains.

The mountain pass is unlit, obviously, and very remote. Once the sun goes down, the path is no longer safe to traverse. There are many tales of machete point robberies of people caught short after wanting to watch the sunset from a distant beach. Once the sun is gone, it’s game over. Your best bet is to swim the few KM around the coast back to Taganga. I have heard many stories of people being taken for everything they’re worth, including being led to ATMs in the town. No point fearing the police when there aren’t any.

However, the boatmen of Taganga make a healthy income by charging only a few pounds per person to ferry people back and forth between the main town and the small coves. If you’re caught out on one of the small beaches, you can always hail them as they go past. They won’t let you walk back.

A fish market for the ages

My first experience with the fish market of Taganga was as I walked by the beach on the local side of town around 6 or 7 pm. I saw a crowd gathered on the sand, obviously interested in something. Not one to turn down a spectacle, I joined them, hoping for a body being pulled or something equally fun. However, it was way more rad.

One of the fishermen had pulled in a shark and was cutting it up and selling it off piece by piece. I am sure most of you will be disgusted and disturbed, but Taganga was known for its shark, both in oil and empanada form. Here it was, live, on the beach, for the fans.

After this, I discovered there is a daily fish market that starts when the various fishermen pull their catches in around 4 onwards. I started frequenting, and boy, was it a marvel. Most of the best stuff was already claimed by the better restaurants in the big city, but if you got there just in time, it was a treasure trove of glorious fish.

Landon and I decided to spark up his BBQ a few times and see what we could see on the wooden beachfront tables. We landed gold every time. The first feast was a huge slice of Marlin as thick as my arm. The second round was two massive lobster tails and a fat red Mojarra. We spent a few evenings cooking them up on the grill and drinking wine and beers, very, very happy with our finds. Neither meal cost more than a song.

Daily, these tables would be full of every fruit of the sea, ranging from squid and octopus to creatures even Lovecraft would hesitate to write about.

A Nightlife, of Sorts

If you’re looking for a wild Colombian nightlife scene, Taganaga probably isn’t the location you’re thinking of, but that isn’t to say it isn’t there. You simply need to adjust your expectations and let yourself become a part of it.

Taganga has no club life. If you want to go somewhere with glaringly loud music and cheap drinks, there is a billiards hall at the end of the beach, on the fishing side. The locals will welcome you in, and you’ll have a hell of a time. On my first visit, I got rigorously patted down by a huge pissed fisherman while he demanded I show him where I was hiding my gun. This was to the great amusement of the rest of the Taganagans watching the spectacle. I immediately felt like one of the boys. However, there are no women, and it is lit like a surgery. Where the real fun happens is in the tiendas along the beachside road.

There are bars on the beach, too, and I had a few fantastic nights drinking with the owner of one in particular tucked way down the end. The sparrow-thin woman who ran it I fancied beyond words, but she was very much in love with her husband and child. It didn’t stop her from plying me with drinks, along with the other locals, until well into the morning and well past my money ran out on multiple occasions. She knew I would come crawling in the next day with my money in hand and a head that was in desperate need of a cold hair of the dog.

However, the best nights were in the tiendas of the roadside. From about 4 p.m., these corner shops would get the music going and the cold beers flowing. The process is simple. Get up from your plastic table and chair, head into the shop, and grab what you want from the store, be it a handful of cold beers or a bottle of liquor and mixer. The shopkeep cracks it for you, charges shop prices, and back to your table you go.

Sitting on these tables, alone or with friends, will always result in an adventure of some kind. As people get more and more pissed, and the freaks and weirdos come crawling out of the sea, all sort of mischief occurs. Late-night impromptu coke benders, heated arguments, long-winded diatribes about travels from washed-up nomads. Anything is possible in the neon glow of the fronts of these bodegas, and they’re where I feel at home.

A soft sandy reset

I needed a break, and life provided it. Taganaga went so far beyond simply being a place to unwind and relax, too. The people I met there helped me reaffirm myself as a person. It can become very easy to lose oneself when constantly moving, rarely making any kind of deep connection. Without that medium to be myself and speak frankly and openly, I start to lose a part of who I am.

With Landon and his social tenacity, I gained a huge amount of myself back but I was also able to meet some other very wonderful people. His housemate Scott was an interesting man who came off as somewhat of an enigma. Despite working in construction his whole life, he had successfully taught himself law to fight a negligence case and was now moving on to bigger and better professions using the money he won from the case.

One evening, Landon came back with stars in his eyes. I thought it was because of the TWO lobster tails he had been given at dinner by the waitress in his new favourite restaurant. What I should have been looking at was why he was being given two lobster tails in the first place and why this was his favourite restaurant. It was Lina.

Through Landon, I met Jess and Lina, the jefa and waitress from a very nice restaurant up on the hill. We spend a few nights over at their home, drinking beer and smoking into the night. Lina is Colombian, Jess Peruvian, and we spent the nights cracking ourselves up and sharing stories of our countries.

We sat in the garden of the large house they shared. This was partly because we were smoking and the nights were warm, but also because they had no furniture but beds. Who needs a fridge, chair, coffee machine, or anything else when you eat at work, and the beach is only yards away with all the sand you could possibly want to sit on? The yard was perfect.

Jess is one of the first Peruvians I have properly met, and she is unlike any Latin Americans I have met before. Whether this is indicative of her culture or it’s just her, I will only know when I make my way over there. Either way, it had me hooked. Jess has a bluntness to the way she speaks that is so unlike most other Latin Americans, it’s jarring. Without being rude, she speaks with careful directness and quickly does away with any kind of unnecessary floral language.

However, that isn’t to say the way she speaks is harsh, unimaginative, or rude. In fact, it is quite the opposite. Because of the direct way Jess speaks, her words have gravitas and clarity that make her passion and thoughts clear and provocative. I took great pleasure in getting into conversations about anything and everything with her as we steadily got more and more high in the evenings. She may have also had the darkest eyes I have ever seen.

Both of these women I plan to stay in contact with and hope to see again when I inevitably return to Taganga. Jess isn’t going anywhere, unlike me; she knows a good thing when she sees it.

All good things must come to an end because that’s just how it is

I had to leave eventually, I guess, or I didn’t, but I also did, although I didn’t want to. Landon had been recalled by his company as they tightened the grip on what ‘remote working’ meant. I just had to go for some reason. I can’t really explain why.

It was time to move on, and even now, I wish I was still there. However, I got what I needed from Taganga, like the using slut I am. It was time to find a new place to get myself involved. I don’t know why I left, and what I moved onto was never going to be equal.

My itchy feet can be frustrating sometimes, and I often feel that maybe I should just try to live more in the moment rather than always looking to what’s next. But the time I spent in Taganga and the people I met there changed the way I felt about the life I had chosen to live for the better.

One day, I will buy a plot and build my own late-night Tienda serving the coldest imported Westcountry ciders. I’ll happily wind down my years and be buried in the sands of Taganga.

No responses yet